THE COMPLEXITY OF A LEADERSHIP MOVEMENT

There is more dynamic engagement within the areas of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in orthopedic surgery today than ever before. In addition, over the recent years, health care and corporate institutions alike have approached culture evolution from multiple pathways. For example, many academic departments and companies worked to designate an individual to serve as a DEI leader. In response to the increased emphasis on combating societal injustices and health-related disparities that has occurred since 2020, the rate of appointment of DEI leaders increased dramatically. However, the suboptimal structure and support of this specific leadership position and fatiguing engagement from any corresponding teams have limited the potential of this movement and, in several cases, have led to the turnover of the DEI leader and the dismantling of their teams.1

According to a review by the Orthopedic Diversity Leadership Consortium (www.orthodiversity.org), there are at least three competing forces at play.2 First, effective integration of DEI leadership and teams into traditional organization structure is not fully understood, with little precedent on how diversity-focused positions and committees are defined or supported. Second, while statistics on the low diversity in surgical fields are often published, there is a notable shortage of solution-based resources describing strategies to guide effective initiatives. Third, surgical care environments are multidisciplinary teams, bringing nurses, advanced practice providers, surgeons, technicians, learners, and anesthesiologists into a single setting with a complex, often high-stress culture. Promoting interprofessional collaboration that accounts for the diversity of the team is a critical yet undervalued leadership skill.

To mitigate these underlying challenges to effective, sustainable DEI leadership, organizations can lean into a deeper understanding of the nuances of this domain and explore the best ways to harness the power of having diverse teams on a system level.3 This review will focus on the power of team dynamics when working toward goals of creating healthy, inclusive environments. The author will use parallels from sports to outline pragmatic steps to move forward.

THE POWER OF INTERPROFESSIONAL COLLABORATION

Taking care of patients has never been a solo sport. Leading DEI is not either. Our orthopedic surgical care environments are inherently multidisciplinary, incorporating team members from a variety of specialties and occupations. As such, the culture within surgery is complex and there are potential sources of implicit bias, resource disparity, interpersonal discourse, and isolation. If left unchecked, these culture threats can work against even the best of DEI efforts. A path forward is created when the power of having a variety of backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences aligned toward a common mission is cultivated within a healthy team. This is not an intuitive or easy task.

For many years, the benefits of interprofessional collaboration in health care have been highlighted. In 2010, the World Health Organization declared the essential need for collaborative clinical practice.4 Recently, a research group published on validated frameworks for interprofessional collaboration, focusing on the core competencies that support and enhance the benefits of diverse teams working together.5 A particularly popular framework cited in this study focused on “learning about, from, and with each other” while drawing on the strengths and capacities of team members.

As described earlier, there is power in numbers but only when those numbers are aligned and clear on the mission and vision. This can certainly be applied to DEI leadership and associated team empowerment. The following sections include guidelines that any DEI team, particularly those that are interprofessional, can use to improve effectiveness and sustainability of this critical work. Just as we have learned invaluable leadership lessons from the sports arena, we can also find numerous parallels to DEI leadership.

MOVING FORWARD: THE PLAYBOOK GUIDELINES

At this point, your organization may have already formed a DEI committee, task force, work group, or team. At minimum, the key stakeholders for change and target audiences have been identified. As in sports, it is possible that the leader and team members have been training for this work all their lives. Conversely, perhaps some of them were drafted. Or maybe some of them participated in aspects of DEI work in unofficial capacities earlier in their career paths and decided to take their contributions to the next level. Regardless of the origin story, the team is here, and the hope is that it is an inclusive interprofessional group that brings in perspectives from all different areas of your patient population served, as well as your internal culture. To achieve this optimal reality, there are 4 key elements in the DEI leadership playbook that should be followed.

I: Establish a Common Purpose

I get a group of people who are talented to commit to excellence and to work together as one. That’s where it starts. Different talents, same commitment.

—Michael Krzyzewski (American basketball coach)

In any sports team, it is beneficial to understand the motivations and goals for each player. Indeed, the overall team may have stated mission and goals, but unless you recognize and achieve understanding of what motivated individuals to join a sport or a team in the first place, you may be setting yourselves up for failure. Some people join teams to win championships. Others join for an opportunity to do what they love and inspire others. Others participate because of the innumerable benefits to mental health. It may be all the aforementioned reasons. The combinations of possible motivations are numerous.

Similarly, when it comes to areas of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging, the list of potential areas of passion and focus is extensive. Often “DEI work” is used in an overly simplistic manner as if all DEI efforts are created equal and can be lumped together. In reality, the scope of DEI can be myopic, broad-reaching, or somewhere in between. Box 1 lists examples of the variety of priority areas focused on by orthopedic DEI leaders, highlighting not only a diverse array of subject matter but also a diverse array of target populations. Is the team’s goal recruitment and retention? Or is the team focused on health equity, defined as the state in which everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health?7 If recruitment and retention are key focus areas, which population is the target—students, graduate medical education trainees, faculty, staff, or executive leaders? Or something else altogether? Consider the complexity of establishing a common vision within recruitment alone.

As an early step, a functional DEI team will need to decide which areas will be the foundation of their mission, vision, and goal that all team members can agree upon. While all the potential domains are critical, understanding what universally motivates and creates energy for all team members will improve effectiveness. Further, understanding and validating the personal goals of each team member will create an important level of connectedness.

II: Create Value for the Team

Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire, the power to unite people in a way that little else does. It speaks to youth in a language they understand. Sports can create hope, where there was once only despair.It laughs in the face of all types of discrimination.

—Nelson Mandela (Former President of South Africa and activist)

Box 1: Sample list of potential areas of focus for diversity, equity, and inclusion leaders and teams:

- Diversifying student-faculty pathways (ie, pipeline programs)

- Diversity and inclusion in research and clinical trials

- Gender equity and policies

- Department/company climate and culture

- LGBQTIA+ equity and policies

- Inclusive search and hiring

- Cultural competency education

- Disability access and support

- Supplier diversity

- Community engagement

- Racial/ethnic equity and policies

- Health equity

- Employee well-being

- Employee resource groups (ie, affinity groups)Abbreviation: LGBQTIA+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer or questioning, transgender, intersex, and asexual, or another diverse gender identity

Now that you have created a team corralled together around common mission and goals, it is important to create value around the team that is visible and understood by supporters within and external to the environment. Across the board, sports teams bring value to spectators, fans, coaches, staff, and leagues in some way, shape, or form. Notably, the value is also felt by the teammates themselves. Even the smallest of teams can inspire and create a spark that warrants the time and ticket prices required to support.

Along the same lines, it is important to create value around and within a DEI leadership team. Historically, DEI effort was housed in a silo away from the organization’s main goals and strategic priorities. It was considered volunteer work to be done outside of work hours and without resource support. Thus, the results from well-intentioned efforts were suboptimal, just as they would be for an unrecognized football team playing on unkempt turf and wearing below-regulation uniform padding without a coach.

Today, there is a pervasive call to action for organization leaders to swing the pendulum toward providing adequate resources to DEI leaders and diversity committees. Such resources can come in the form of dedicated time during the work week for team meetings, funding for initiatives and the leadership role, and promotional credit assigned for the members who are contributing to the organizational DEI goals. When these resources are not provided, there is a signal sent to the team and to the rest of the organization that these efforts are neither valuable nor valued. Such a sentiment would be contrary to the numerous studies that prove that there are a multitude of measurable value-added benefits from increasing diversity and belonging within an organization.

For example, in Scott Page’s book, The Diversity Bonus, he presents the mathematical and practical bonuses of having heterogeneous teams when solving complex problems, such as those found in health care.7 A groundbreaking report by McKinsey and Company outlined improved financial outperformance from companies with increased racial, ethnic, and gender diversity on their teams.8 The higher the representation, the higher the likelihood of outperformance. Importantly, patient outcomes have also been improved when inclusion and equity have been embraced by healthcare teams.9

Moving away from the narrative that DEI effort is strictly volunteer work and an under-resourced burden is a necessary step forward. Specifically, identifying a wide variety of support, including designation of executive sponsors, and ascribing value to the leader and team will aid in effectiveness, relevance, and sustainability. The value proposition is clear and should be amplified to attract others to engage and contribute.

III: Measure Your Outputs… Inclusively

If winning isn’t everything, why do they keep score?

—Vince Lombardi (National Football League executive and coach)

There is an age-old debate about whether keeping score in youth sports is a necessary part of teamwork and skill development or an unnecessary evil that can destroy self-confidence with very little to no benefit. Proponents of scorekeeping argue that keeping score promotes the development of the lifelong ability to cope with a miss or a loss. However, at the core, the purpose of having a score is not simply to determine who is winning and who is losing but rather to define measurements and goals that can be universally accepted as expectations.

In the DEI arena, having advanced metrics to define goals and expectations is surprisingly new. Traditional DEI goals barely measured any outcomes and, if they did, the focus was primarily on representation data. How many women are in a residency program? How many underrepresented minority physicians are in a practice? What percentage of researchers in a department identify a disability? For years, representation data have informed recruitment strategies, which in turn informed advancement initiatives, which then informed attrition mitigation methodology. And the cycle repeats. However, despite decades of emphasis on representation metrics, there continues to be significant disparity within orthopedics, and medicine in general, specifically in the areas of in pay equity, promotion, leadership enactment, inclusion and belonging, and resource allocation. In fact, there are fewer black men in medicine today than there were 40 years ago.10

So, why is not focusing solely on representation metrics enough? Well, just like the final score of a playoff game shows the outcome but not the heart and sweat displayed on the field, representation data alone do not give a holistic picture of the components of an environment that formulate a culture of belonging, equity, and respect. To truly investigate, understand, and then communicate a current state and measure trends, additional metrics must be incorporated in a thoughtful fashion. Start by looking at the data that are already collected in your organization and inquire whether demographic filters can be applied. For example, in our organization, the patient experience scores collected are housed in an easily accessed dashboard for each provider to review their individual reports. In 2021, a toggle field was created to apply various domains of demographic filters to assess for any relevant differences in communication and experience domains across populations. Modern culture surveys have incorporated intentional questions around belonging to assess whether employees and practitioners truly feel as if they can be authentic in the workplace. Industries outside of health care have endorsed measuring community partnerships and total dollars invested in DEI initiatives.

Box 2 lists some examples of DEI metrics that may be relevant to your team, based on your common mission and goals and the value of DEI effort expected by your organization. Regardless of the metrics selected, ensure that (1) they are indeed measurable, (2) they cannot be artificially manipulated, and (3) they incentivize/promote desirable behaviors. The sweet spot combination of metrics should be relevant for your particular environment and will bring greater clarity and insight to your team’s activities.

IV: Co-create Your Strategy

A lot of people notice when you succeed, but they don’t see what it takes to get there.

—Dawn Staley (American basketball player and coach)

The official flag football arm of the National Football League created basic instructions for teams on how to create an effective playbook.11 The instructional document identified the purpose of creating a playbook as a method of keeping a team’s strategy consistent and organized from the beginning to help players build the fundamental skills necessary to have a successful season. In addition, they asserted that as players grew and gained confidence, the playbooks should be adapted, reorganized, and rearranged.

Box 2: Sample list of potential diversity, equity, and inclusion metrics topic areas:

- Demographic representation in clinical teams

- Demographic representation in senior leadership

- Patient Experience Scores

- Culture and Belonging Scores

- Pay equity gap closure

- Retention of clinicians and staff

- Implementation of inclusive hiring practices

- Community based organization partnerships

- Minority-serving institutions/HBCU partnerships

- Participation in professional development programs for underrepresented groups

- Financial support for DEI leader and team resources

- Resolution of professionalism complaints

- Social determinants of health measures

- Employee Well-Being Scores

- Engagement of employee resource groups (ie, affinity groups)Abbreviations: DEI, diversity, equity, and inclusion; HBCU, Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

This advisement rings true for determination of DEI strategy. It is tempting to ask a consulting group to provide a “copy and paste” strategic plan that will bring peace and harmony to all aspects of your organization. As discerned from the sections discussed earlier, this approach generally does not work. Each environment—and each team will have a unique set of opportunities, a nuanced history, and a variety of characteristics that warrant a customized “playbook” be developed to achieve in the areas of DEI.

Indeed, foundational templates of a strategic plan are a great starting point for most organizations. However, the blanks should be filled in by the leadership and team members based on internal assessments and input from stakeholder groups. In fact, the act of creating a strategic plan and working together to form your unique playbook can foster cohesion and honest introspection that is more valuable than the actual end-product of a plan. As a first step, your team should understand what a strategic plan is and the benefit it provides. In a provocative article, business researcher Graham Kenny called out the reality that most strategic plans are not strategic and are likely not even plans.12 He describes a common misinterpretation of “objectives” and “actions” as “strategy.” Understanding these important points can bring more intention to designing the plan that will help your group reach its DEI goals in a sustainable format.

Strategy creation technique: the KJ method

Whenever possible, co-create your strategic plan with the members of the DEI team and invite members of marginalized or underrepresented groups to participate as well. In 2022, our team utilized a unique methodology to help us identify and focus on relevant strategic priorities toward the future. Referred to as the “KJ Method,” or “KJ Technique” this approach to creating cohesive solutions was developed by Japanese ethnographer Jiro Kawakita13 This technique can be used by teams to generate ideas and identify priorities. As such, it is considered one of the most popular brainstorming exercises. There are 2 critical components to this exercise: creation of an affinity diagram and subsequent formation of an intergraph.

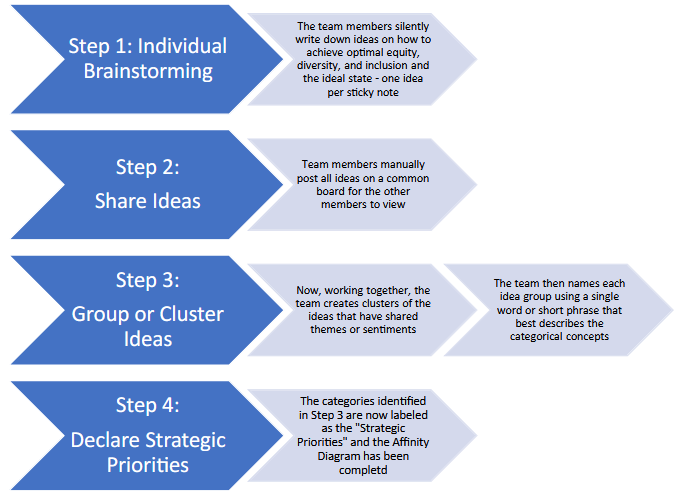

Fig. 1. Steps of the K-J technique to facilitate collective team brainstorming toward the identification of strategic diversity, equity, and inclusion priorities. This phase of the exercise is also referred to as the creation of an affinity diagram. (Adapted from Lucid. K-J Technique.2023, Retrieved from https://www.lucidmeetings.com/glossary/kj-technique.)

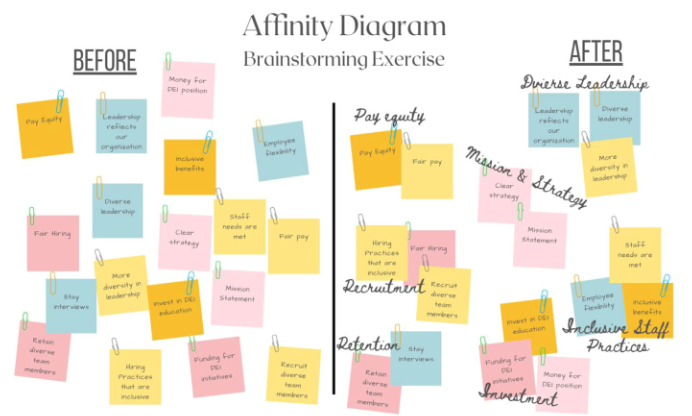

The steps for creation of an affinity diagram are outlined in Fig. 1 and can be applied to any subject matter for a team, especially DEI. This is a proven technique for taking seemingly disjointed ideas and reframing them in an organized fashion. For this first stage of the exercise, teams are asked to individually identify key features of their optimal state, such as a diverse, inclusive, and equitable environment. The members of the group do this in silence, writing a single phrase or sentence on individual sticky notes. Once completed, the various notes are pasted to a board and the members can visualize all of the generated descriptors from their colleagues. If there are descriptors that are similar, such as “fair pay” and “pay equity,” those respective notes are grouped together. Hence, an affinity diagram is generated by the team with various groupings that are subsequently assigned agreed upon category labels (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Affinity diagram creation. Initially, the ideas generated from the brainstorm appear random and disorganized. The team works together to group similar ideas into clusters and then creates their own labels for the groupings, forming categories which will be declared as the strategic priorities.

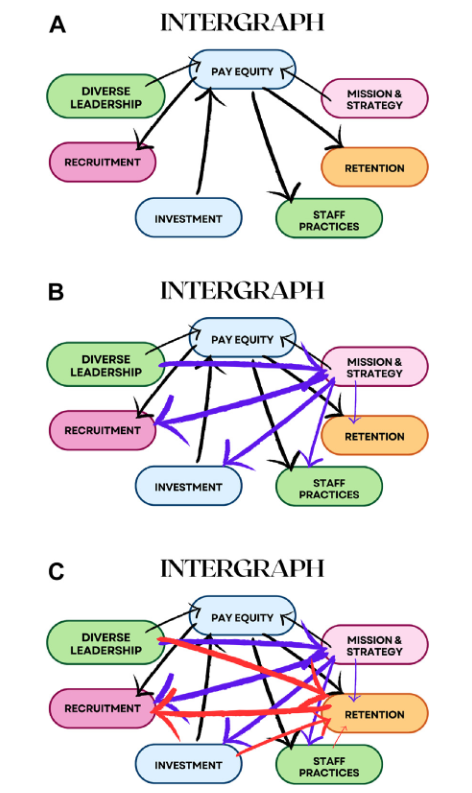

Once the affinity diagram is completed, the team will recognize that they have identified categories that represent the key components to achieve their optimal state of DEI. The team is now ready to create an intergraph, a graphic representation of the relationship between various priority categories. This is a powerful part of the experience, as the team evaluates each pair of categories and determines which category of a pair is the “driver” and which category is the “receiver.” For example, when comparing “diverse leadership” and “pay equity,” the group collectively decides which of the two categories drives the other. Does diverse leadership lead to pay equity? Or does pay equity lead to diverse leadership? This decision will be unique for each environment. A graphic of a developing intergraph is shown in Fig. 3(A–C).

Fig. 3. Intergraph creation. Using the categories generated from the affinity diagram, a team can construct an intergraph to identify the key drivers toward attaining their diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) goals. Each individual category is compared to the rest, with the team considering in which direction the relationship arrow should be drawn. In (A), the black arrows compare “Pay Equity” to the remaining categories and identify the “driver” and the “receiver” of the pair through the direction of the arrows. In (B), the purple arrows compare “Mission and Strategy” to the remaining categories. In (C), the red arrows show the relationship between “Recruitment” and the other categories. This continues until each relationship direction between all the categories is determined. At the end of the exercise, the categories with the most arrows departing from them are considered the top drivers, and the categories with the most arrows pointing toward them are considered the top receivers.

In summary, the KJ Method is just one approach that a team can take to co-create strategic priorities for their action plan that are inherently relevant and insightful. From our group’s experience, we were able to uncover our internal drivers that, while traditionally underscored, were critical priorities for us to elevate to achieve our mission toward a diverse, equitable, and inclusive health system. While we previously focused on recruitment and retention and assumed they were the main drivers toward diversity and inclusion, the KJ Method exercise actually identified leadership training, pay equity, investment into DEI, accountability, and data acquisition as areas much more instrumental in driving us toward our goals than recruitment. Most importantly, this discovery was created by us and for us, and therefore garnered broad buy-in for the execution of the resulting strategic plan.

SUMMARY: OPTIMIZE SUSTAINABILITY

When you run the marathon, you run against the distance, not against the other runners and not against the time.

—Haile Gebrselassie (Olympic runner)

The DEI leadership and team experience has evolved in response to a very dynamic state of change in our society. More industries are recognizing the power of incorporating lenses of equity, inclusion, diversity, and belonging into their operational business domains. In health care, we are recognizing and embracing the importance of integrating these lenses into the fabric of how we deliver care and build our teams. As in sports, you can have the most powerful, talented players on a team, but endurance is just as important.

In this review, the author has outlined four necessary components of empowering DEI leaders and teams, including solidifying a common mission, creating value around the team and its purpose, measuring relevant and inclusive outputs, and co-creating a strategy that is meaningful and effectively achieves your true north. When these components are combined and facilitated, sustainability and effectiveness can be increased. We all want to be part of a winning team. The author would suggest that if you have supported a DEI leader and forged a team built on grace, connectedness, and intentional humanism, you have already won.

Onward.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to acknowledge my father, the late, great Charley Taylor – a former NFL Professional football player, NFL Hall of Famer, and an inspiration for many. As one of the first Black players to integrate the Washington Football Team in the 1960s, soon after Bobby Mitchell, his superhuman talents, leadership, and grace paved the way for others. Breaking these barriers, and many records, took the team to new heights that are still recognizable today. His legacy will continue to inspire all of us.

DISCLOSURE

Consultant, Johnson & Johnson DePuy Synthes. Other relationships/Speaker: Stryker, Total Joint Orthoapedics, Exactech.

REFERENCES

- Cutter C, Weber L. Demand for chief diversity officers is high. so is turnover. Wall St J 2020.

- Taylor E, Dacus R, Oni J, et al. An introduction to the orthopaedic diversity leadership consortium. J Bone Joint Surg 2022;104(72):1–4.

- Ely R, Thomas D. Getting serious about diversity: enough already with the business case. Brighton, MA: Harvard Business Review; 2020.

- (WHO), W. H. (2010). Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice. Geneva.

- McLaney E, Morassaei S, Hughes L, et al. A framework for interprofessional team collaboration in a hospital setting: Advancing team competencies and behaviours. Healthc Manage Forum 2022;35(2):112–7.

- Braveman, P. A. (2017, May 17). What is health equity? and what difference does a definition make? Retrieved from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2017/05/what-is-health-equity-.html.

- Page S. The diversity bonus: how great teams pay off in the knowledge economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2017.

- McKinsey. (2020). Diversity Wins: How Inclusion Matters.

- Gomez L, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J Natl MedAssoc 2019;111(4):383–92.

- Laurencin C, Murray M. An american crisis: the lack of black men in medicine. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2017;4(3):317–21.

- NFL-Flag. How to create a winning flag football playbook 2023. Available at: https://nflflag.com/coaches/default/flag-football-rules/football-playbook.

- Kenny G. Your strategic plans probably aren’t strategic, or even plans. Harvard Business Review; 2018. Available at: https://hbr.org/2018/04/your-strategic-plans-probably-arent-strategic-or-even-plans.

- Scupin R. The KJ method: A technique for analyzing data derived from Japanese ethnology. J Hum Rights 1997;56(2):233–7.